Episode #16 Experiencing Grief, Loss, and Radical Uncertainty with Roshi Joan Halifax

For many months, grief has been at the forefront of our collective global consciousness. We have been pushed to confront a world of uncertainty from the tragic loss of millions of lives, to the loss of social relationships and identity, to the sudden disruption of daily structure. The events of the last year have certainly been a lesson in impermanence.

Our guest on this episode is Roshi Joan Halifax, a Buddhist teacher, Zen priest, medical anthropologist, and author of Being with Dying. She is the founder, Abbott, and headteacher of Upaya Zen Center, a Buddhist monastery located in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Roshi Joan contributed to many pioneering practices in end-of-life care and continues to teach compassionate care of the dying.

Roshi Joan offers perspective on how loss shapes us and why dying is a rite of passage. Dr. Maizes asks Roshi Joan what Buddhist philosophy can teach us about acceptance and what practices or experiences might help us recover from this period of grief while we prepare for a new way of being post-pandemic. We discuss the unprecedented healthcare crisis and the practitioners at the front lines. Dr. Weil reflects on past historical events and how suffering is inherently a part of life and why grieving matters. Roshi Joan explains why cultivating compassion in times of pain can be of tremendous service to all.

Please note, the show will not advise, diagnose, or treat medical conditions. Always seek the advice of your physician or healthcare provider for questions regarding your health.

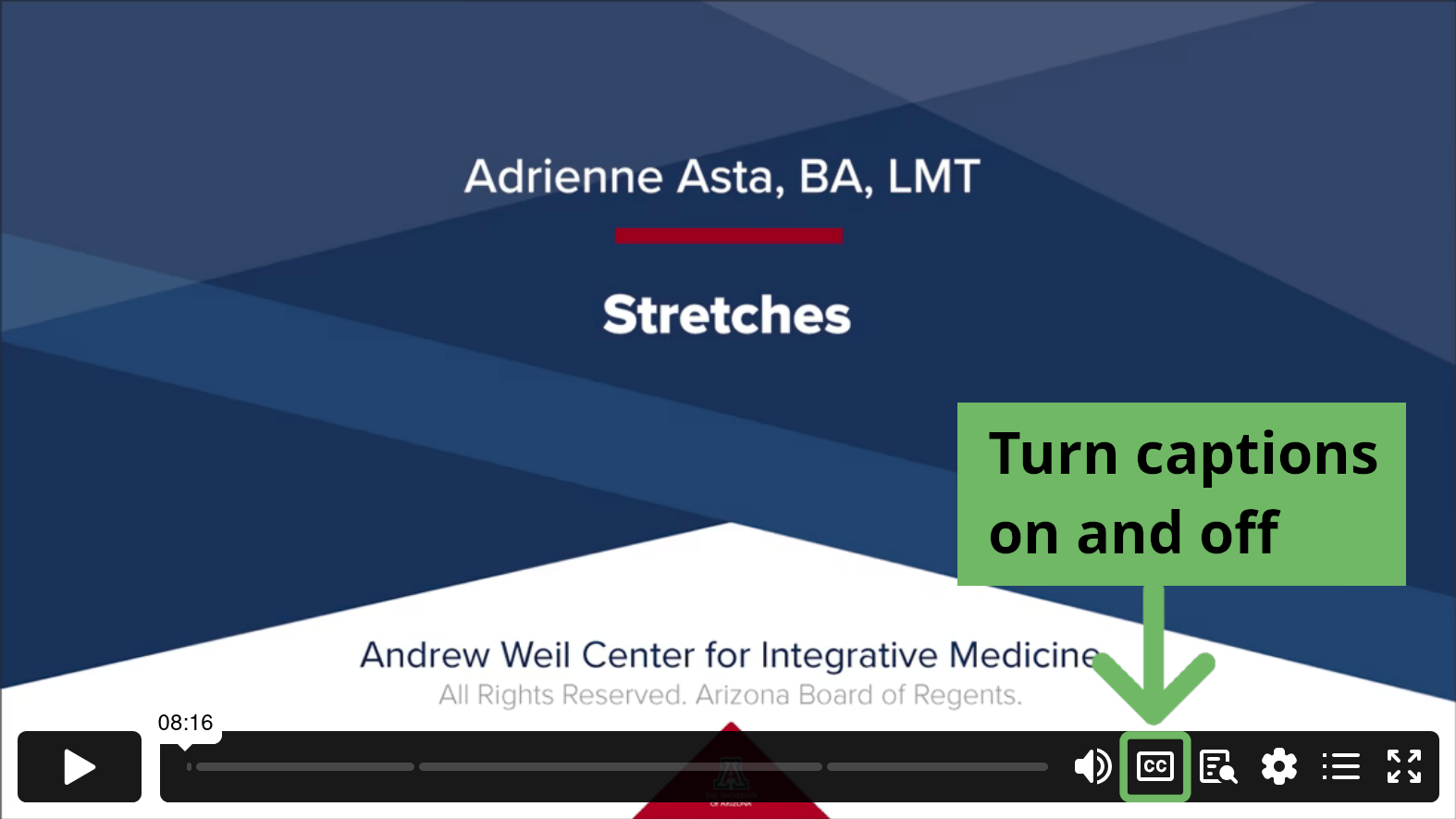

Play Episode

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Hi, Andy

Dr. Andrew Weil: Hi Victoria.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Today, we're going to speak with someone you've known for a really long time Roshi. Joan, how effective

Dr. Andrew Weil: Actually I've known her in several incarnations. First she was an anthropologist who studied shamans in various cultures. Then did work with psychedelics and therapy. And finally found a home in as a Buddhist.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Yeah. And so she, it has so much wisdom to share with us about what we're experiencing collective right now, collectively right now end of life collective grief. And so I really want to learn from her, so let’s welcome her on.

Intro Music

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Roshi Joan Halifax is a Buddhist teacher, Zen priest, anthropologist and author. She is founder Abbott and head teacher of Upaya Zen center, a Buddhist monastery in Santa Fe. New Mexico. Roshi Joan received her PhD in medical anthropology in 1973, from 1972 to 1975 she worked with psychiatrist Stan Graph at the Maryland psychiatric research center, where they did pioneering work with dying cancer patients using LSD as an adjunct to psychotherapy. Roshi Joan has continued to work with dying people and their families, and to teach compassionate care of the dying her work and practice for more than four decades has focused on engaged Buddhism.

Welcome Roshi Joan.

Joan Halifax: Thank you so much, Victoria. Very nice to be with you again and to see my old friend, Andy.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: So I want to begin with a quote from one of your books, Being With Dying, you wrote, “I witnessed again and again, how spiritual and psychological issues leap into sharp focus for those facing death. I discovered caregiving as a path and as a school for unlearning the patterns of resistance, so embedded in me and in my culture.”

So in addition to all your other qualities, you are a wonderful storyteller. And I'm wondering if you could begin to bring this into focus for us with a story.

Joan Halifax: Yeah, I'm happy to try. You know, I remember when Stan and I were working with dying people using LSD as an adjunct to psychotherapy. There was an older woman who had metastatic breast cancer. And we were very close. I, I really felt so aligned with her. And I think she felt that way toward me as well. And at one point she looked at me really strongly, just right deep into my eyes. And she said, you can never know what it's like to die. And I have to tell you, it was one of those moments where I experienced a kind of it was like an arrow to the heart or it's sort of awakening.

She was right. And my role was to come alongside her experience and to have the kind of internal arms to hold whatever was present for her. And I also realized that she was a teacher for me. And she really opened the path of learning from dying people. That I actually, the only thing that I could bring to people who were dying wasn't good advice.

It was presence. It was presence that maybe was characterized by care and courage. So I will always feel a bit of love in a certain way for what she taught me. And from that point on, I felt I was a student to people who were dying.

Dr. Andrew Weil: Roshi Joan, I have to ask you what do you think of the renaissance of LSD and psychedelics?

I mean, it's been a long time coming and there's a lot of interest in LSD assisted psychotherapy. Do you still see this as a useful tool, the woman who was the head of palliative care at the University of Arizona said to me a short while ago that it just killed her, that she could not use that tool with dying patients because the law is preventative at the moment. What do you think about that?

Joan Halifax: So it's a very powerful substance is, as you are well aware Andy, and I think that from the point of view of the work that Stan and I did in the early 1970s, and with great attention to set and setting also with Stan's earlier work in using LSD in a psycholytic context, you know, with multiple doses of smaller amounts, but he learned so much about the human unconscious so that that was needless to say very important in the attitude that we brought into the interaction with dying cancer patients. I think it's a powerful tool. And as such every powerful tool has its great benefits and also has enormous challenges.

And so, you know, using LSD specifically as an adjunct to psychotherapy, which was our approach at that time was done with such meticulousness such care. And we kind of programmed the whole scene if you will, for a positive outcome, even if during the context of the, the LSD session itself, the dying cancer patient you know, encountered difficulties, but we were able to contextualize those experiences in a positive way to frame those experiences in a positive way. So I don't feel like the casual use of it with dying people is recommended. Also I think that Bill Williams, who was part of our project then who is now and has been part of the Hopkins East Bay project and continues the work using not LSD, but psilocybin.

I have a feeling psilocybin is a little more merciful. Then the quote single overwhelming dose of 600 micrograms of LSD, which, you know, produced to a pretty overwhelming effect. So I, you know, I have a feeling that psilocybin is a better medium and but and, and it's something, I think it would be valuable to ask Bill his opinion.

This is just my opinion drawn on my experience from decades ago. But I, I think it's worthwhile. It's not for everybody. And honestly, Andy, when Stan and I went our separate ways I wanted to continue working with dying people, which I did. And also, I realized that the experience of dying involved a really profound transformation of consciousness, and that may be wasn't necessary to actually amplify things to the degree that we did at the research center, but the outcomes of the research were consequential. They were very positive. And again, I think, you know, we were invested as therapists and researchers in producing positive outcomes. So, you know, we just entered into these relationships wholeheartedly.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: So aside from psychedelics. Given the enormous cultural fear that people have about dying, the avoidance of thinking about one's own death, that's most typical, I'd say in our culture. What else can people do to prepare? I think in some ways the virus has forced most people to contemplate death in a very different way than has been typical in American society.

Joan Halifax: Yeah, I think you're, you're quite right. You know, the exploration of our mortality you know, from the point of view of Plato is kind of a bedrock of spirituality. And in whether you're a Christian or a Buddhist or a Jew it is not about avoiding that bedrock. It's actually about exploring it. Deeply. And you're quite right in our culture, which is not true of all cultures, where we have let go of the rites of passage that produce a maturation for individuals from birth adolescence childbirth marriage, et cetera, et cetera, through right on through the dying process. We don't have those rites of passage, which give one the kind of existential opportunity, the lived experience of what it means to go through death and rebirth. And so the, the lack of examination of oneself and of the very fundamental existential perspectives that abide within the psyche. But are unexplored it's really now we're up against the wall, you know? Well, globally we're looking at over 2 million deaths in our own country. We're over at this point, at this time of this interview well, over 300,000 deaths, I believe. And so in a way, death is on our shoulder all the time anyway, but now with this pandemic, we're really pushed either to look at what death means, how we could, can die well, and also what it means to actually explore our mortality, not as something that is terrifying, but it's actually liberating.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Andy, I'm wondering from your life experience, how you might answer that question about what could the average human being do to prepare for their own death? What practices, what experiences?

Dr. Andrew Weil: I don't know that I'm an expert on that, Victoria, but I would say the main practice is to constantly be aware of your mortality.

You know, and not to try to shut that out of your consciousness, which is the habit most of us fall into you know, one extreme form of that is a Buddhist practice of meditating or into practice also of meditating in graveyards that's extreme. But even to see a corpse, you no, in men, in medicine, I very rarely saw a patient actually die.

That was mostly something that nurses, you know, saw. And but I think that let the, the reality of death into your life. Not to try to exclude it is really important. I would say, I think about my mortality every day in some way or other, and I think that's a good practice. I heard Deepak Chopra recently say that he was doing a meditation practice of trying to really experience the world when he was gone. What would reality be like when he was no longer existing? I mean, there are all sorts of things like that one can do.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: One of the things that I have done is during Shavasana, which is the very last pose in a yoga class, it's sometimes called corpse pose. I think about being gone, being an actual corpse. And usually the first thing that happens is I think of my mother. Who died very unexpectedly. And for many years I was actually very comforting that my mother's image would come to me at the end of a yoga class. And I would think I'm gone and I'm going to be with this loved person in my life. And then when my father died, I was like, what do I do now? And I had a yoga teacher who said, well, how about breathe in mom and breathe out, dad? You know, there was a way in which I was trying to, you know, hold. You know the presence of both of these obviously Seminole people in my life in that moment. But the other thing that I really noticed is the letting go of burden.

Like, okay, there are all these things I'm carrying, but if I'm dead, someone else picks them up, doesn't pick them up, but they're no longer mine.

Joan Halifax: Yeah. That's wonderful, Victoria.

There are specific practices in Buddhism that give one the opportunity to actually explore psychophysical, if you will. The dying process it's called the dissolution of the elements where the earth element dissolves into water, water, into fire, fire, into air, air, into space. And each of those relates to what are called the, on this form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness, pool space. And then the, and it's very powerful in our Being with Dying Training. We actually just a few days before the end of the training and I'm always a little quakie doing it. You know, the 60 physicians and nurses on the floor of our Zendo in the sleeping lion position being taken through this very powerful visualization.

And I'm always like, oh my gosh, if they knew that you were going to be doing this where they. And they get CMS, but anyway, do this in the process of this training they, they might not have the, you know, signed up, but anyway that has been a really one of the most powerful things about the training, partly it's because the community, there's a great deal of trust, feeling of safety.

We've explored things, you know, deep, we get to that particular. Practice people are you know, very open to exploring things. But it is, you know, the Tibetans kind of nailed it. And though it's done while one is you know, before one is active, dying process. What is fascinating about that particular practice is that if you have sat with dying people or you've had a huge case of flu or you've been with people who are very ill or the aging process, it kind of tracks psychologically from the point of view of that sensory experience. And also physically what happens as one unbinds from this world.

And there's another practice. Oh, I want to mention before I mentioned this other practice one of the things that I think is interesting is that in, at the so-called death point, they're inter-disillusions, but death from the point of view of Tibetan Buddhism is understood to be the ultimate moment for liberation, for freedom.

And I think it's, you know, it's like instead of being some kind of uni-directional, gravitational surface, where you're just shot into, you know, whatever forgetfulness and so on, it's the opportunity, the greatest opportunity for awakening, for liberation. And so that the practices that one has done, you know, for one's whole life prepares one for that moment, that big you know, the extraordinary phase shift that occurs around dying and death. But another thing that I have comes from earlier Buddhism which was described in the on upon society suitor is actually you mentioned Andy, the Charnel ground meditation. It is actually visualizing yourself as a or a corpse as some yourself or someone else's recently deceased.

And then you go through the process of decay and finally to dust, and it brings back one of the really important teachings in Buddhism and that and it's one of the most essential realizations, and that is the realization of a truth of impermanence. That there's nothing that we can hold on to.

Everything is going to go including our very Sun. So I'm understanding how impermanence is a constant it will prevail. Our end is inevitable. And there are other practices, which I don't need to discuss here to make a whole thesis of it. But anyway Buddhism, you know, I was born and raised in a Christian family and I was an anthropologist and I also was very spiritually inclined and very curious. And I just hunted all over religions for a frame of reference that would bring the existential elements related to our mortality, into focus. And I found no other religion that gave practices and views that were as useful as those fountain Buddhism. So I ended up being a kind of Buddhist.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Yeah, Buddhism seems to have the clearest roadmap. And if one's belief system or adopted belief system, is there maybe it's easier, you know, if you absolutely take that in but in our dominant Judeo-Christian culture, people I think remain very frightened and don't have practices. And I know that our students are regularly asking, can you give me a script? You know, what can I say? What can I ask someone? Because of course they're all expected to have a conversation about code status. And if people have a living will, and have they thought about the end of their life, and they're expected to do that, not just with someone who's terminally ill, but as a part of their care and their unbelievably uncomfortable.

Joan Halifax: Well, yes, of course. And I think that's one of the things, whether it's a doctor or a nurse or a hospitalist or a patient advocate this is, I think, why the work that we've done at Upaya and also my buddy, Frank Ostaseski she's the best. You know those of us who've been in this field a long time and, and working with healthcare providers, trying to really help healthcare providers develop the capacity to actually address these existential questions, but not as experts. Again, going back to this woman who died breast cancer to really be able to come alongside, you know, when people ask me, well, what happens after you die? I'll pause. And I'll say, “well, let me know your thoughts about that.

Dr. Andrew Weil: Hmm. Can I ask you for, I'd be interested to hear what you have to say about near death experiences and you know, what you think about that and is there anything we can learn from them?

Joan Halifax: You know, years ago, actually, I think it was 1970, no, sorry. 1992. I was in Dharamsala with his holiness, the Dalai Lama in a small conference call, sleeping, dreaming, and dying with Francisco Varela and people who worked in the field of consciousness.

And it was very, I was asked to do the presentation on near death experiences. So, you know, I got Kenneth ring and I, yeah, I did all this research and I was very interested in the field because it's an important area because people who experience NDEs frequently end up being very altruistic. You know, they come back there's a sense of meaning of life of having a meaningful life of purpose, a sense of deep gratitude of, you know, having seen something which was extraordinary, perhaps you know, the relatives on the other side, beckoning them and so forth. So in any case you know, I, I did the whole sort of contour, the NDE.

And his holiness listened very attentively. And then I said, you know, what, what, what do you think about this, your holiness? I'm just, I'm curious, is this anything, you know, that relates to the Bartow total to the Tibetan book of the dead? And he's he's so he was so sharp. He said those are near death experiences, not death experiences. I really had to chuckle. I was hoping for a more spectacular answer either to say, but now I, I am very congruent with his response. I, I really, I have to say I burst out laughing and quite right. I think that he, an NDE is like going through an extreme rite of passage and can have very positive outcomes for a person who's experienced it.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: I'm wondering if we could shift a little bit and talk about grief.

There's so much grief right now. There are all of the people who have died in our country, worldwide. There are people who have been ill and haven't regained their health. There are people who are still reeling from the deaths of George Floyd and others.

And I think an awakening to the racial injustice, that's so prevalent. There's loss of jobs. And therefore also loss of identity, there's loss of our social relationships, because most of us are spending a lot of time sheltered alone, or with just a few people who we considered ourselves close to.

Dr. Andrew Weil: It may be that there is a conservation of suffering and grief and that no matter what, at what point in history you live, if you look at it, that that is the nature of experience.

And certainly that is, you know, one of the Buddhist great insights is that at the core of life is suffering. And I suspect that at any point you think, you know, that my parents lived through World War II and the Great Depression. And I, I just wonder that if at any point there is not this kind of tremendous amount of suffering and grief, the forms may change.

Joan Halifax: You know, Andy, I think that's a very important point. And on the other hand, there's something. So in your face about this pandemic, Yeah. And yeah, there's something so in one's face around the second World War around the bombing of Hiroshima, Nagasaki around various plagues and wars that have circled our, our globe, but I think that Victoria is pointing towards something else that is important that would also, you know, relate to the depression and to war and that is that the sense of radical uncertainty. That people are experiencing that is now global it's shared, it's really shared around the world. And also another thing, for example, there are more people in lockdown today than there were alive during the second world war and where our social relations are actually often perceived as threats to our wellbeing. So, you know, you, you, somebody delivers groceries to your car and you're masked up and you're just hoping that they haven't coughed on the bag, so to speak. So, you know, there's a different kind of wariness that I at least in my lifetime and you and I are more or less the same age.

I think Andy, I don't know how old are you now? Shall I say, Oh, me too. That's right. Yeah, we share, we share the same.

Dr. Andrew Weil: A distinction about this time may be the global awareness of it. You know, we did not in the past have social media. We did not have television news linking us all together. When you look at the 1918 flu, which had a much higher mortality people in one part of the country, weren't aware of what was going on in another country.

So I think there's this kind of global awareness of the situation and make it something makes it different.

Joan Halifax: And I think also Andy, the loss of our daily structure the loss of social contacts multiple losses, millions of jobs people savings and homes, you know, have been you know, that figures into the account.

Equation and things like people not being able to see their loved ones. You know, like my friend, Maya, whose parents are in an elder care facility in the Southern part of Santa Fe where she can't even access her parents. And they're both positive and…

Dr. Andrew Weil: What about people dying alone and not being able to see their, their immediate relatives?

Joan Halifax: And the effects of this, for example, on healthcare providers. And that's something, you know for decades is as you know, NDI said at the bedside of dying people, but also for decades, I've been working with healthcare providers or with clinicians, doctors, and nurses, and the moral suffering that clinicians are experiencing in having to be, you know, surrogates, if you will.

Also of not being able to access adequate resources to even take care of their patients. So there's the sense of the loss of moral ground. Which is another grief that people are encountering. So I feel that we're grieving the loss of, of a whole way of life, but it's also showing us.

Many things, including you know, who our friends really are, who we really care about how important our relationships are how fortunate for those of us who are currently free the virus that we can have relative health often because of privilege is also showing us the racism in our country, the classism in our country.

So it's, you know, it's a time we're in, you know, this kind of liminal world. We're not out of this. I've said quite often in the past six, eight months that it's like a global rite of passage that we're experiencing right now. We don't know what the outcome will be, but we don't think we'll be going back to the old normal.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: So as someone who's been engaged in active Buddhism not, not sitting in a cave, but rather taking all the teachings and putting them into action in the world as we can come out into the world are there steps we can take to recover from what we've experienced and maybe to create a different world?

Joan Halifax: Yeah. You know I, I remember something that Terry Tempest Williams wrote, she said, good. If my, a good friend of mine said you are married to sorrow. And I looked at him and said, I'm not married to sorrow. I just choose not to look away. And I think it's really important that we not look away. This time that we're in is I doubt if in the lifetime, even of younger people, a hundred years, a little over a hundred years since the great plague of 1918.

Yeah. The pandemic of 1918, this is so radical. So wild. What we're in it is global. We're so hyper-connected, and yet we're distant. Our mortality is right in our face. Uncertainty is now our way of life. We have no idea what is ahead and as a result of that what we're seeing and, you know, this is kind of wild, you know, Upaya is this beautiful very intensively placed the practice here in this case. But what has happened is that there are literally thousands and thousands of people who have now opted into our community in order to practice in order to explore the truth of suffering in order to understand something about their relationship with dying and death and so forth.

So, you know, it's bringing people, if you will, to the source of what it means to be, I feel truly human.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Andy, you have spoken about how you learned about the 1918 flu epidemic because your grandmother told you stories about it. And yet it mostly is not a story we've told very often in our society. I mean, I know there was a, a book. I don't remember now whether it's a decade ago or 15 years, the great influenza, but we mostly actually didn't bear witness. I think we mostly put the lid on it as fast as we could.

Dr. Andrew Weil: You know, I was, I don't know how old I was, but I, it seems to me I was something in the realm of seven eight, nine, ten that my grandmother used to tell me these stories of Philadelphia, which was the hardest hit city on the East coast.

And she told me these stories of horse-drawn carts of corpses going through the streets of Philadelphia… I, that made a very strong impression on me and it sounded like something out of the middle ages. And I, when I was in high school, I tried to get information on that and there was none. It was as if this had been culturally repressed because it was such a heavy experience that people couldn't deal with it.

Joan Halifax: Gosh, Andy, that is such an interesting observation, you know, I wonder what that did to the generation that came out of that pandemic. What, what do you think?

Dr. Andrew Weil: You know, also that that pandemic was distinctive in that it killed, selectively, killed young, healthy people. And tended to spare the old and very young.

So that must've been an especially frightening. It was people in their twenties and thirties who were in the picture of health, had a headache in the morning and were dead in the evening. Must've been unbelievably frightening. And as I say, I think it was culturally repressed for many, many years. And it wasn't really until the 1990s, I think that scientists began looking into the question of why that flu was so deadly and thinking you got what was special about the virus. Nobody had paid any attention.

Joan Halifax: But I'm also curious, Andy, your thoughts on how this would affect the psychosocial landscape, for example, of the mid-twenties to the mid-thirties.

Dr. Andrew Weil: Well remember also this came right at the end of world war I. So double whammy

Joan Halifax: And right before World War II, and the rise of fascism.

Dr. Andrew Weil: Yeah. So that must've been a very formative event for, you know, people in our parents' generation.

Joan Halifax: Well, I mean, do you think there's any relationship for example, about the presence of the pandemic and a more, well, this might be too far out for us to talk about in this context, but you know, what's happening in this country politically at this time.

Dr. Andrew Weil: Well, I think when people are afraid and there's great uncertainty, there's a tendency to gravitate toward those who tell you how it is and to make sense of things and seem to represent order and stability. And maybe that does, that is a you know, something that leads people toward fascism and leaders who espouse that kind of philosophy.

Joan Halifax: Anyway, interesting observation.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: So I'd love to hear closing thoughts on what would help us with the grief. Especially, you know, we, we, as you do train a lot of healthcare professionals and while suffering may always be a part of life they are seeing more deaths than. Is at all common for doctors, for doctors in training. And they have been really brought to the brink.

One of our faculty who works with residents, Patricia Levinson told me recently that they're beyond burned out. They, they just have suffered and seen so much suffering. And I want to know what we can do. I haven't been providing hospital care. What can we do to help heal?

Joan Halifax: Well, this is, it's a really powerful question Victoria, and you know, one thing I want to say is that it is essential I believe at this point to acknowledge the moral suffering that clinicians are experiencing, including, you know, moral distress, moral injury. Moral outrage and moral apathy, or, you know, the numbing out experience and also feeling experiencing moral disengagement and identifying you know these domains of of of harm internal harm that arise from confronting the dying in the magnitude that clinicians are confronting and not having the internal resources.

Or the external resources to provide adequate care. So it's a violation if you will, of one's own vows as a clinician and they, I believe that we will be involved for a long time in repair., in addressing these harms to one's sense of you know, what, one's very character. Now I, you know, I know at at your place, at my place, there's a big emphasis on the value of contemplative practice in terms of in engendering insight, but also most importantly the, the importance of compassion and, you know, years ago, I did a heuristic map of compassionate and then developed a tool called Grace, which allows people in a very direct way to cultivate compassion while they're interacting with with others.

And these kinds of practices, I feel are really important to share with clinicians. And for, for also for clinicians to understand that compassion is a win-win-win situation that is, we know now from the point of view of neuroscience and social psychology that I'm experiencing. Compassion has interesting health benefits and also psychological benefits.

We also know that people who receive compassion are benefited, and we also know that people who witness. Those who are compassionate, feel morally elevated and want to engage in acts of altruism and compassion. So I think one of the really important things for us to do in this process. Confronting trauma that clinicians, many clinicians are experiencing and all suffering that many clinicians are experiencing and naming it, working with it skillfully is to actually provide the tools for clinicians to go back into service with more capacity.

And those tools, I think many of them are not just in this sort of simple algorithms of giving care, but they have to do with the development of internal qualities related to attention and intention, insight and so forth.

Dr. Andrew Weil: I think it is useful. Always to remind oneself and others that grief and grieving or normal processes, they are in fact healing processes. That is the way that we come to terms with loss and suffering, accept them and move on from them. And it becomes a problem when people get stuck in some phase of grief and we can help them out of that.

But I think realizing that that is absolutely normal reaction and a desirable one. And it is in fact that healing process.

Joan Halifax: Andy, I think this point is really important the normalization of grief and to understand, you know, from the point of view of positive integration of trauma that it, it actually enhances our character.

And I look on grief the experience of grieving is one of the most humanizing of our human experiences. For example, it's the blessing of humility to know that loss is inevitable and the cherishing of relationships and the development of moral character and the experiences you suggest, Andy, that spiritual transformation is often the outcome of grief.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Well, that seems like a very hopeful and beautiful note to end on that the grief can lead to transformation of character. I want to thank you so much for spending this time with us Roshi Joan, we are deeply appreciative.

Joan Halifax: Thank you. It's so great to see my old buddy. We're old now Andy.

Well, thank you.

Dr. Victoria Maizes: Good to see you. I want to just one last thing I heard you say on something someplace you were interviewed, that grief is love that has nowhere to go. And I wondered whether that's why so many people are reaching out to your center, because if we can come together, communally, you know, gives it a place to go.

Joan Halifax: I think that yeah, this is what I'm experiencing now. This extraordinary intimacy, even though we are physically distant one from another, but we are through this fascinating technology able to meet each other in ways that we never anticipated. And we've been driven together by the pandemic and the suffering in this world.

Thank you. Thank you. Stay well, thank you so much. Bye bye.

Hosts

Andrew Weil, MD and Victoria Maizes, MD

Guest

Joan Halifax

@bodyofwonderpodcast

www.facebook.com/bodyofwonderpodcast

@bodyofwonder

Connect with the Podcast

Join the Newsletter

Be the first to know when there is a new episode.

Send the Show Your Questions

Submit a question for our hosts or suggest a topic for future episodes. We'll try to answer as many questions as we can on the show.